-40%

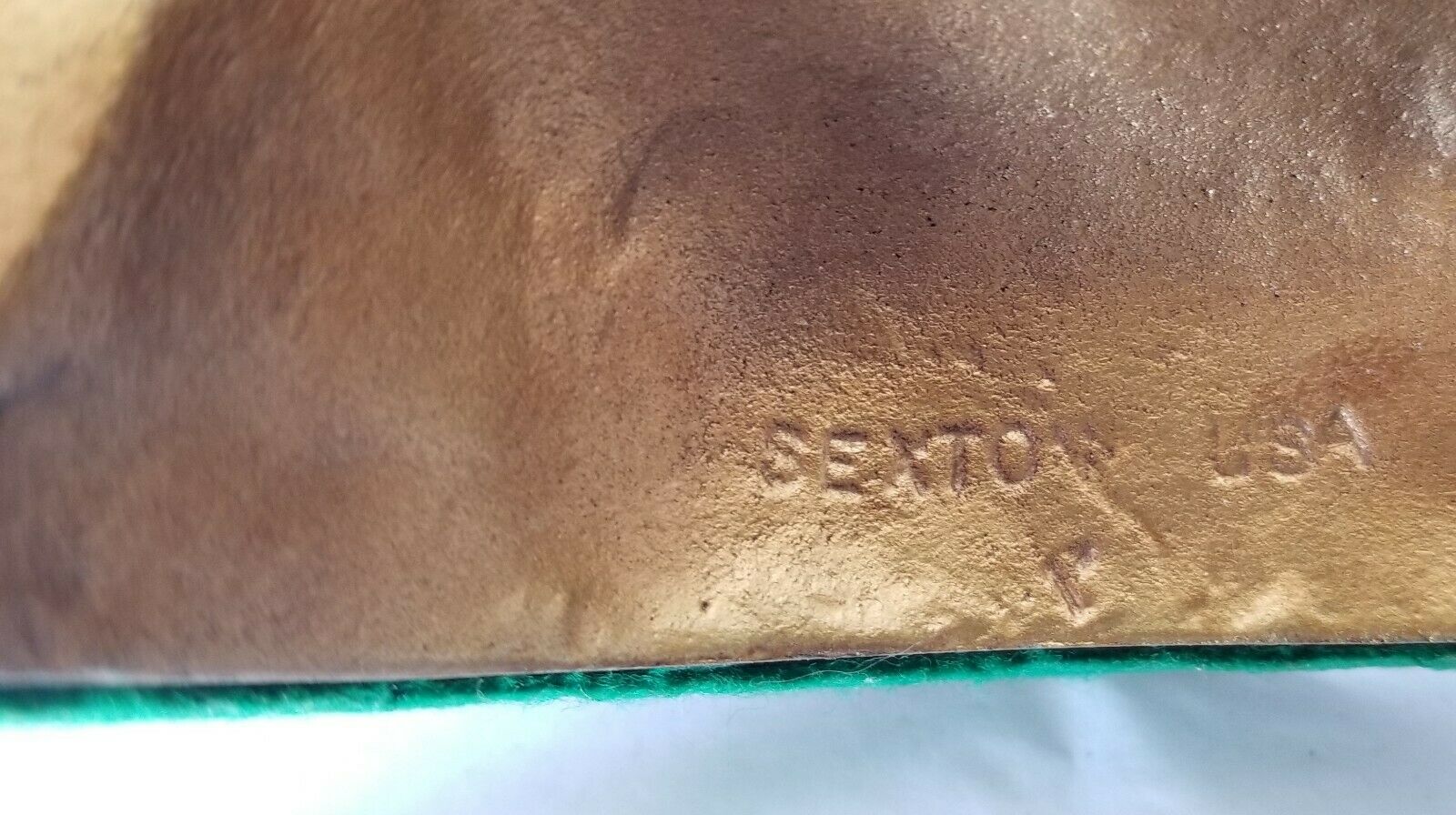

SEXTON BICENTENNIAL EAGLES on 4 STAR BASE BOOKENDS DOORSTOP- HEAVY CAST METAL

$ 26.4

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

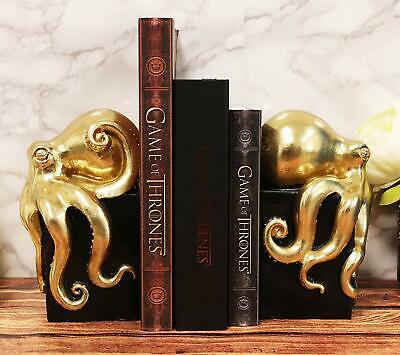

HEAVY CAST METAL Bookends: BI-CENTENNIAL EAGLE STANDING ON 4 STAR BASE bookends. They each measure 6" by 8" & nice condition, original paint. Matching pair. Still have the original GREEN felt on the bottoms.Stamped on the reverse of each one is " SEXTON USA " Insured USPS Priority mail delivery in the Continental US is $ 15.50. Will ship Worldwide and will combine shipping when practical.

Common in

libraries

, bookstores, and homes, the

bookend

is an object tall, sturdy, and heavy enough, when placed at either end of a row of upright

books

, to support or

buttress

them. Heavy bookends—made of

wood

,

bronze

,

marble

, and even large

geodes

—have been used for centuries; the simple sheetmetal bookend (originally patented in 1877 by William Stebbins Barnard)

[1]

uses the weight of the books standing on its foot to clamp the bookend's tall brace against the last book's back; in libraries, simple metal brackets are often used to support the end of a row of books. Elaborate and decorative bookends are common as elements in

home decor

.

The word "bookends" is also used metaphorically to refer to any pair of items which frame and define a significant or noteworthy event or place. For example, regarding the practice in the

United States

whereby

Memorial Day

and

Labor Day

demarcate the traditional beginning and end of

summer

, those two

holidays

could be referred to as bookends.

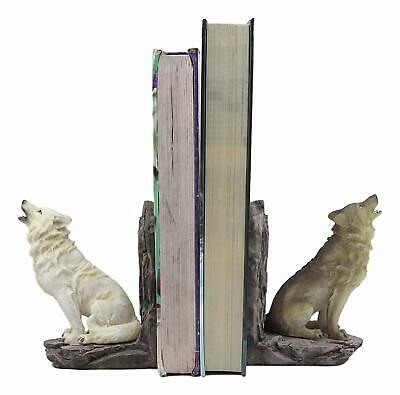

A good book can enrich a mind, spur a life-changing epiphany, or transport a reader to a minutely detailed universe hatched from an author’s imagination. A good pair of bookends can’t promise all that, but they can sure add a lot of character to a room. Bookends are like punctuation marks on a shelf, proclaiming the importance their owners place on the tomes in between.

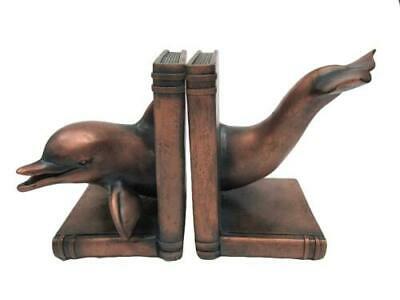

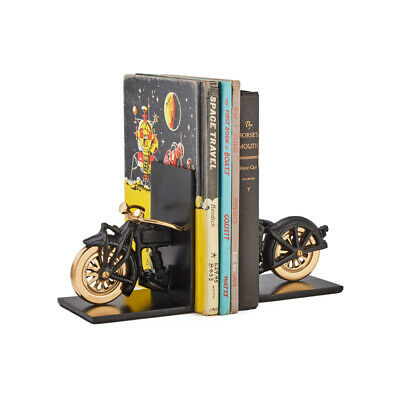

Many antique and vintage bookends share a key trait—they're heavy, often made of weighty materials such as wrought iron, ceramic, carved stone, or cast metal. Solid bronze bookends are especially popular and collectible, sometimes resembling small, paired pieces of sculpture rather than utilitarian devices to keep books from sliding off a shelf.

Bronze was a favorite material of Art Deco-era artists and designers, who used everything from female nudes to reproductions of Rodin’s “Thinker” for bookends. From the 1920s through the 1950s, a New Jersey company called Marion Bronze, as well as its predecessor, Pompeian Bronze, was famous for its painted bronze bookends.

Of the ceramic bookends, collectible examples include pieces by

Roseville

and

Rookwood

in the United States, and Clarice Cliff and PenDelfin in the U.K. The Roseville bookends from the 1930s shaped like open books, with a pine bough and cone propping open the “book,” are particularly prized.

Metal bookends ranged from hammered copper pieces made by

Roycroft

craftsmen during the Arts and Crafts period to cast brass animal figures. Then there were the stone bookends, which were sometimes paired with metals (bronze and marble was a typical combination in the 1920 and ’30s) or used solo—onyx and alabaster are just two examples of stones favored by artisans from Mexico to Asia.

The bookend is an object tall, sturdy, and heavy enough, when placed at either end of a row of upright books, to support or buttress them. Heavy bookends—made of wood, bronze, marble, and even large geodes—have been used in libraries, stores and homes for centuries; the simple sheetmetal bookend (originally patented in 1877 by William Stebbins Barnard)[1] uses the weight of the books standing on its foot to clamp the bookend's tall brace against the last book's back; in libraries, simple metal brackets are often used to support the end of a row of books. Elaborate and decorative bookends are common as elements in home decor. The word "bookend" is also used metaphorically to refer to any pair of items which frame and define a significant or noteworthy event or place. For example, regarding the practice in the United States whereby Memorial Day and Labor Day demarcate the traditional beginning and end of summer, those two holidays could be referred to as bookends. Bookends are usually made by metal and plastic.

Early libraries did not need bookends. People arranged books horizontally into the 16th century (and perhaps longer). Only once enough books existed to fill up a bookshelf—which only started to resemble the furniture of today in the 16th century—without falling over did libraries begin to store books vertically.1 It took even longer for people to shelve books spine-out. Many Medieval and Renaissance libraries chained books to lecterns and shelves; in order to attach the chain without causing damage, these libraries stored books fore-edge out. In the 16th century, books began to include authors and titles on their spines, though not universally, a sign that shelving practices included spine-out configurations. By the next century, nearly all books had bibliographic information on their spines.1 Bookends are a relatively new technology. The familiar L-shaped metal kind were first patented in the 1870s.1 It took some decades before the term became common parlance: the Oxford English Dictionary records 1907 as the first year the term “book end” appeared in print.2

A doorstop (also door stopper, door stop or door wedge) is an object or device used to hold a door open or closed, or to prevent a door from opening too widely. The same word is used to refer to a thin slat built inside a door frame to prevent a door from swinging through when closed. A doorstop (applied) may also be a small bracket or 90-degree piece of metal applied to the frame of a door to stop the door from swinging (bi-directional) and converting that door to a single direction (in-swing push or out-swing pull). History Formally-produced doorstops trace their history to the 18th century in Europe, becoming widely manufactured in Europe in the early 19th century. By the mid 19th century, manufacturing had primarily moved to the United States.[1] Despite their early manufacturing, credit for the invention of the doorstop is usually granted to Osburn Dursey, an African Americans inventor, in 1878. The doorstop was Dursey's most famous invention and he received a US patent, number 210,764, for the invention.[2] Usage Holding doors open A door may be stopped by a doorstop which is simply a heavy solid object, such as a rubber, placed in the path of the door. These stops are predominantly improvised.[1] Historically, lead bricks have been popular choices when available.[3] However, as the toxic nature of lead has been revealed, this use has been strongly discouraged.[4] Another method is to use a doorstop which is a small wedge of wood, rubber, fabric, plastic, cotton or another material. Manufactured wedges of these materials are commonly available. The wedge is kicked into position and the downward force of the door, now jammed upwards onto the doorstop, provides enough static friction to keep it motionless.[5] A third strategy is to equip the door itself with a stopping mechanism. In this case, a short metal bar capped with rubber, or another high-friction material, is attached to a hinge near the bottom of the door opposite the door hinge and on the side of the door which is in the direction that it closes. When the door is to be kept open, the bar is swung down so that the rubber end touches the floor. In this configuration, further movement of the door towards being closed increases the force on the rubber end, thereby increasing the frictional force which opposes the movement. When the door is to be closed, the stop is released by pushing the door slightly more open, which releases the stop and allows it to be flipped upwards. A newer version of equipping the door with the stopping mechanism is to attach a magnet to the bottom of the door on the side which opens outward which then latches onto another magnet or magnetic material on the wall or a small hub on the floor. The magnet must be strong enough to hold the weight of the door, but weak enough to be easily detached from the wall or hub.[6]

The United States Bicentennial was a series of celebrations and observances during the mid-1970s that paid tribute to historical events leading up to the creation of the United States of America as an independent republic. It was a central event in the memory of the American Revolution. The Bicentennial culminated on Sunday, July 4, 1976, with the 200th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence.

Contents

1

Background

2

Ceremonial coinage

3

Logo

4

1975 events

5

Events

6

The Bicentennial on screen

6.1

Television

6.2

Films

7

Gifts

8

Gallery

9

See also

10

Notes

11

References

12

Further reading

13

External links

Background

The nation had always commemorated the Founding as a gesture of patriotism and sometimes as an argument in political battles. Historian Jonathan Crider points out that in the 1850s, editors and orators both North and South claimed their region was the true custodian of the legacy of 1776, as they used the Revolution symbolically in their rhetoric.[1]

The plans for the Bicentennial began when Congress created the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission on July 4, 1966.[2][3][4][5] Initially, the Bicentennial celebration was planned as a single city exposition (titled Expo '76) that would be staged in either Philadelphia or Boston.[6] After 6½ years of tumultuous debate, the Commission recommended that there should not be a single event, and Congress dissolved it on December 11, 1973, and created the American Revolution Bicentennial Administration (ARBA), which was charged with encouraging and coordinating locally sponsored events.[7][8][9][10] David Ryan, a professor at University College Cork, notes that the Bicentennial was celebrated only a year after the withdrawal from Vietnam in 1975 and that the Ford administration stressed the themes of renewal and rebirth based on a restoration of traditional values, giving a nostalgic and exclusive reading of the American past.[11]

Ceremonial coinage

Main article: United States Bicentennial coinage

Reverse of the Bicentennial quarter, minted 1975–1976.

Reverse of the Bicentennial half dollar, minted 1975–1976.

Reverse of the Bicentennial dollar (Type 1), minted 1975–1976.[12]

Reverse of the Bicentennial dollar (Type 2), minted 1975–1976.

Logo

NASA's Vehicle Assembly Building in 1977

Bruce N. Blackburn, co-designer of the modernized NASA insignia, designed the logo. The logo consisted of a white five-point star inside a stylized star of red, white and blue. It was encircled by the inscription American Revolution Bicentennial 1776–1976 in Helvetica Regular. An early use of the logo was on a 1971 U.S. postage stamp. The logo became a flag that flew at many government facilities throughout the United States and appeared on many other souvenirs and postage stamps issued by the Postal Service. NASA painted the logo on the Vehicle Assembly Building at the Kennedy Space Center in 1976 where it remained until 1998 when the agency replaced it with its own emblem as part of 40th anniversary celebrations.[13]

1975 events

The American Freedom Train when stopping in the Naval Air Station in Miramar, California on January 15, 1976.

The official Bicentennial events began April 1, 1975, when the American Freedom Train launched in Wilmington, Delaware to start its 21-month, 25,388-mile (40,858 km) tour of the 48 contiguous states.[14]

On April 18, 1975, President Gerald Ford traveled to Boston to light a third lantern at the historic Old North Church, symbolizing America's third century.[15] The following day, April 19, he delivered a major address in Concord, Massachusetts at the Old North Bridge where the "shot heard round the world" was fired, commemorating the 200th anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord which began the military aspect of the American Revolution.[16]

On December 31, 1975, the eve of the Bicentennial Year, President Ford recorded a statement to address the American people by means of radio and television broadcasts.[17] Presidential Proclamation 4411 was signed as an affirmation to the Founding Fathers of the United States principles of dignity, equality, government by representation, and liberty.[18]

Events

Festivities included elaborate fireworks in the skies above major American cities. President Ford presided over the display in Washington, D.C. which was televised nationally. A large international fleet of tall-masted sailing ships gathered first in New York City on Independence Day and then in Boston about one week later. These nautical parades were named Operation Sail (Op Sail) and witnessed by several million observers. The gathering was the second of six such Op Sail events to date (1964, 1976, 1986, 1992, 2000, and 2012). The vessels docked and allowed the general public to tour the ships in both cities, while their crews were entertained on shore at various ethnic celebrations and parties.

In addition to the presence of the 'tall ships', navies of many nations sent warships to New York harbor for an International Naval Review held the morning of July 4. President Ford sailed down the Hudson River into New York harbor aboard the guided missile cruiser USS Wainwright to review the international fleet and receive salutes from each visiting ship, ending with a salute from the British guided missile destroyer HMS London. The review ended just above Liberty Island around 10:30 am.

Several people threw packages labeled "Gulf Oil" and "Exxon" into Boston Harbor in symbolic opposition to corporate power, in the style of the Boston Tea party.[19]

Johnny Cash was the Grand Marshall of the U.S. Bicentennial parade.[20]

First Lady Betty Ford, with President Ford, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip in the President's Dining Room in conjunction with a 1976 state visit during the U.S. Bicentennial.

The event was attended by Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip. The Royal couple made a state visit to the United States, toured the country and attended other Bicentennial functions with President and Mrs. Ford. Their visit aboard the Royal Yacht Britannia included stops in Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., Virginia, New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts.

While in Philadelphia on July 6, 1976, Queen Elizabeth presented the Bicentennial Bell on behalf of the British people. The bell is a replica of the Liberty Bell, cast at the same foundry—Whitechapel Bell Foundry—and bearing the inscription "For the People of the United States of America from the People of Britain 4 July 1976 LET FREEDOM RING."[21]

Local observances included painting mailboxes and fire hydrants red, white, and blue. A wave of patriotism and nostalgia swept the nation and there was a general feeling that the irate era of the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War and the Watergate constitutional crisis of 1974 had finally come to an end.

In Washington, D.C., the Smithsonian Institution opened a long-term exhibition in its Arts and Industries Building replicating the look and feel of the 1876 Centennial Exposition. Many of the Smithsonian's artifacts dated from the 1876 World's Fair in Philadelphia which commemorated the 100th anniversary of the independence of the United States. The Smithsonian also opened the new home of the National Air and Space Museum July 1, 1976.

NASA commemorated the Bicentennial by staging a science and technology exhibit housed in a series of geodesic domes in the parking lot of the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) called Third Century America. An American flag and the Bicentennial emblem were also painted on the side of the VAB; the emblem remained until 1998, when it was painted over with the NASA insignia. NASA planned for Viking 1 to land on Mars on July 4, but the landing was delayed to July 20, the anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing. On the anniversary of the signing of the Constitution, NASA held the rollout ceremony of the first Space Shuttle (which NASA had planned to name Constitution but was, instead, named "Enterprise" in honor of its fictional namesake on the television series Star Trek[22]).

Douglas DC-8 of Overseas National Airways in U.S. Bicentennial special livery.

Many commercial products appeared in red, white, and blue packages in an attempt to tie them to the Bicentennial. Liberty, a brand of Spanish olives, sold their product in glass jars replicating the Liberty Bell during that time. Products were only permitted to display the trademarked Bicentennial logo by paying a license fee to ARBA.

Many national railroads and shortlines painted locomotives or rolling stock in patriotic color schemes, typically numbered 1776 or 1976, and model railroad manufacturers quickly released bicentennial locomotives which were popular among children and adults. Many military units marked aircraft with special designs in honor of the Bicentennial.

Disneyland and The Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World presented America on Parade, an elaborate parade celebrating American history and culture, and featured the Sherman Brothers' song "The Glorious Fourth". The parade featured nightly fireworks and ran twice daily from June 1975 to September 1976.

John Warner, later U.S. Senator from Virginia, served as ARBA director.[23]

The New Jersey Lottery operated a special "Bicentennial Lottery" in which the winner received ,776 per week (before taxes) for 20 years (a total of ,847,040).

The overall theme of the entertainment of Super Bowl X, held January 18, was to celebrate the Bicentennial. Players on both teams, the Pittsburgh Steelers and the Dallas Cowboys, wore a special patch with the Bicentennial Logo on their jerseys; the Cowboys also added red, white and blue striping to their helmets throughout their bicentennial season. The halftime show, featuring the performance group Up with People, was entitled "200 Years and Just a Baby: A Tribute to America's Bicentennial".

The United States Olympic Committee initiated bids to host both the 1976 Summer and Winter Olympic Games in celebration of the Bicentennial. Los Angeles bid for the 1976 Olympics but lost to Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Denver was awarded the 1976 Olympic Winter Games in 1970, but concern over costs led Colorado voters to reject a referendum to fund the games and the International Olympic Committee awarded the games to Innsbruck, Austria, the 1964 host.[24] As a result, there was no Olympics in the United States in 1976 despite a last minute offer from Salt Lake City to host. However, Lake Placid would host the 1980 Winter Olympics, Los Angeles would eventually be awarded the 1984 summer games, and Salt Lake City would also eventually be awarded the 2002 Winter Olympics.

President Ford (center) with Darrell Johnson and Sparky Anderson during ceremonies at the 1976 Major League Baseball All-Star Game

As site of the Continental Congress and signing of the Declaration of Independence, Philadelphia served as host for the 1976 NBA All-Star Game, the 1976 National Hockey League All-Star Game, the 1976 NCAA Final Four, and the 1976 Major League Baseball All-Star Game at which President Ford threw out the first pitch.[25] The 1976 Pro Bowl was an exception and was played in New Orleans, likely due to weather concerns.

George Washington was posthumously appointed to the grade of General of the Armies of the United States by the congressional joint resolution Public Law 94-479 passed January 19, 1976, with an effective appointment date of July 4, 1976.[26] This restored Washington's position as the highest-ranking military officer in U.S. history.[Note 1]

The Bicentennial Wagon Train Pilgrimage began a journey from Blaine, Washington on June 8, 1975 concluding at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania on July 4, 1976.[27][28] The wagon train pilgrimage traced the original covered wagon trade and transportation routes across the United States encompassing the Bozeman Trail, California Trail, Gila Trail, Great Wagon Road, Mormon Trail, Natchez Trace Trail, Old Post Road, Old Spanish Trail, Oregon Trail, Santa Fe Trail, and Wilderness Road.[29][30]

Karen Steele was the first baby born on July 4, 1976, 12 seconds after midnight, and was referred to as the "Bicentennial Baby". She was featured on The Today Show and Good Morning America, and received commemorations from President Ford, New Jersey Governor Brendan Byrne, and a host of other notables.

The Bicentennial on screen

Television

Related network television programs aired July 3–4, 1976

The Great American Celebration, 12-hour syndicated entertainment program hosted by Ed McMahon and airing the night of July 3

The Inventing of America (NBC), two-hour BBC co-production reviewing 200 years of American technological innovations and their impact on the world, co-hosted by James Burke and Raymond Burr[31][32]

In Celebration of US (CBS), 16-hour coverage hosted by Walter Cronkite

The Glorious Fourth (NBC), 10-hour coverage hosted by John Chancellor and David Brinkley

The Great American Birthday Party (ABC), hosted by Harry Reasoner

Happy Birthday, America (NBC), hosted by Paul Anka from the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum

Bob Hope's Bicentennial Star-Spangled Spectacular (NBC)

Best of the Fourth (NBC), recap with John Chancellor and David Brinkley

July 4 satellite broadcast of the University of North Texas One O'Clock Lab Band live performance in Moscow (NBC), sponsored by the US Department of State

Days of Liberty (WABC – New York), animated holiday special

Goodbye America (PBS), mock "newscast" re-enacting a 1776 debate in the House of Commons concerning the future of the American colonies

The Bicentennial Minute was a series of short vignettes aired on CBS from 1974 through the end of 1976 to mark the occasion.

Saturday morning Bicentennial programs

In the months approaching the Bicentennial, Schoolhouse Rock!, a series of educational cartoon shorts running on ABC between programs on Saturday mornings, created a sub-series called "History Rock", although the official name was "America Rock". The ten segments covered various aspects of American history and government. Several of the segments, most notably "I'm Just a Bill" (discussing the legislative process) and "The Preamble" (which features a variant of the preamble of the Constitution put to music), have become some of Schoolhouse Rock's most popular segments.

In 1974, CBS aired a new animated Archie series on Saturday mornings called The U.S. of Archie; 16 episodes were made and were shown in reruns until September 1976.

Films

For the Bicentennial celebration, Hollywood filmmaker John Huston directed a short movie—Independence (1976)—for the U.S. National Park Service which continues to screen at Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia to the present day (2018).

The 1976 film Rocky cited the Bicentennial in several scenes, mostly during Apollo Creed's entering; Carl Weathers dressed first as George Washington then as Uncle Sam.