-40%

MAN SITTING ON BOOK READING BOOKENDS - DOORSTOP- CAST METAL

$ 18.48

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

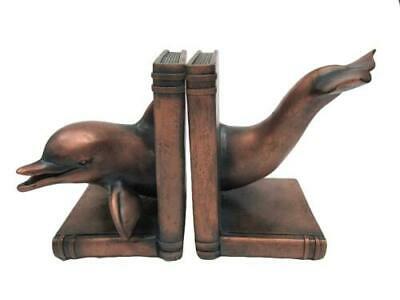

Cast Bookends: MAN SITTING ON A BOOK READING A BOOK BOOKENDS. They each measure 3.5" X 5". Finish or paint has come off of one of them. Appears to be a bearded man in a night cap or a wizard. Not sure. Screw bottom. Weigh approximately 5 pounds.Insured USPS Priority mail delivery in the Continental US is $ 15.50. Will ship Worldwide and will combine shipping when practical.

Common in

libraries

, bookstores, and homes, the

bookend

is an object tall, sturdy, and heavy enough, when placed at either end of a row of upright

books

, to support or

buttress

them. Heavy bookends—made of

wood

,

bronze

,

marble

, and even large

geodes

—have been used for centuries; the simple sheetmetal bookend (originally patented in 1877 by William Stebbins Barnard)

[1]

uses the weight of the books standing on its foot to clamp the bookend's tall brace against the last book's back; in libraries, simple metal brackets are often used to support the end of a row of books. Elaborate and decorative bookends are common as elements in

home decor

.

The word "bookends" is also used metaphorically to refer to any pair of items which frame and define a significant or noteworthy event or place. For example, regarding the practice in the

United States

whereby

Memorial Day

and

Labor Day

demarcate the traditional beginning and end of

summer

, those two

holidays

could be referred to as bookends.

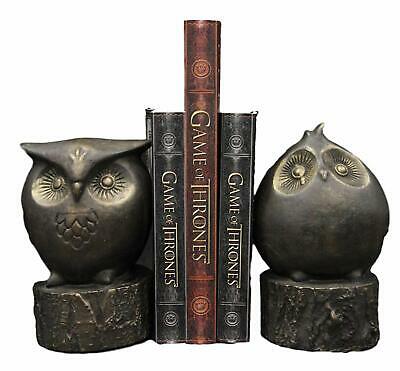

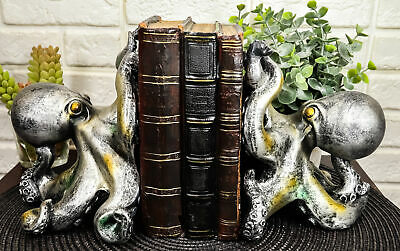

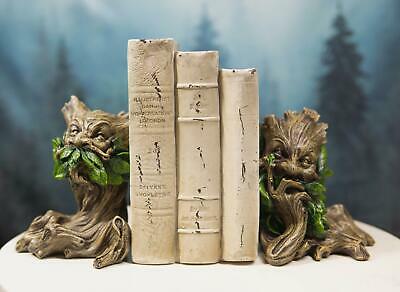

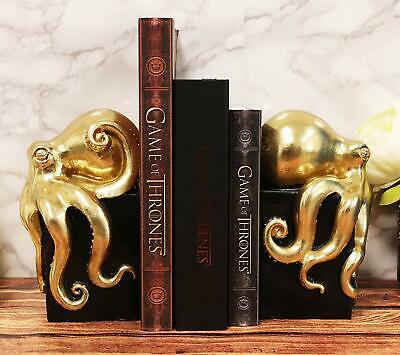

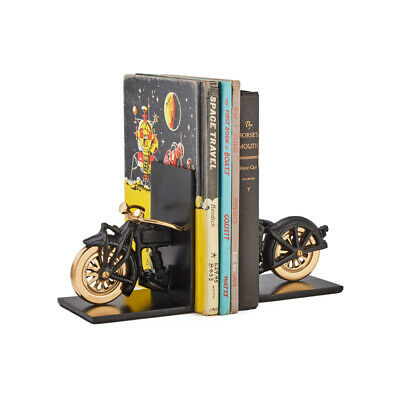

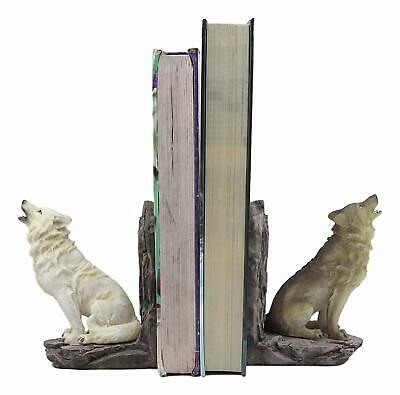

A good book can enrich a mind, spur a life-changing epiphany, or transport a reader to a minutely detailed universe hatched from an author’s imagination. A good pair of bookends can’t promise all that, but they can sure add a lot of character to a room. Bookends are like punctuation marks on a shelf, proclaiming the importance their owners place on the tomes in between.

Many antique and vintage bookends share a key trait—they're heavy, often made of weighty materials such as wrought iron, ceramic, carved stone, or cast metal. Solid bronze bookends are especially popular and collectible, sometimes resembling small, paired pieces of sculpture rather than utilitarian devices to keep books from sliding off a shelf.

Bronze was a favorite material of Art Deco-era artists and designers, who used everything from female nudes to reproductions of Rodin’s “Thinker” for bookends. From the 1920s through the 1950s, a New Jersey company called Marion Bronze, as well as its predecessor, Pompeian Bronze, was famous for its painted bronze bookends.

Of the ceramic bookends, collectible examples include pieces by

Roseville

and

Rookwood

in the United States, and Clarice Cliff and PenDelfin in the U.K. The Roseville bookends from the 1930s shaped like open books, with a pine bough and cone propping open the “book,” are particularly prized.

Metal bookends ranged from hammered copper pieces made by

Roycroft

craftsmen during the Arts and Crafts period to cast brass animal figures. Then there were the stone bookends, which were sometimes paired with metals (bronze and marble was a typical combination in the 1920 and ’30s) or used solo—onyx and alabaster are just two examples of stones favored by artisans from Mexico to Asia.

The bookend is an object tall, sturdy, and heavy enough, when placed at either end of a row of upright books, to support or buttress them. Heavy bookends—made of wood, bronze, marble, and even large geodes—have been used in libraries, stores and homes for centuries; the simple sheetmetal bookend (originally patented in 1877 by William Stebbins Barnard)[1] uses the weight of the books standing on its foot to clamp the bookend's tall brace against the last book's back; in libraries, simple metal brackets are often used to support the end of a row of books. Elaborate and decorative bookends are common as elements in home decor. The word "bookend" is also used metaphorically to refer to any pair of items which frame and define a significant or noteworthy event or place. For example, regarding the practice in the United States whereby Memorial Day and Labor Day demarcate the traditional beginning and end of summer, those two holidays could be referred to as bookends. Bookends are usually made by metal and plastic.

Early libraries did not need bookends. People arranged books horizontally into the 16th century (and perhaps longer). Only once enough books existed to fill up a bookshelf—which only started to resemble the furniture of today in the 16th century—without falling over did libraries begin to store books vertically.1 It took even longer for people to shelve books spine-out. Many Medieval and Renaissance libraries chained books to lecterns and shelves; in order to attach the chain without causing damage, these libraries stored books fore-edge out. In the 16th century, books began to include authors and titles on their spines, though not universally, a sign that shelving practices included spine-out configurations. By the next century, nearly all books had bibliographic information on their spines.1 Bookends are a relatively new technology. The familiar L-shaped metal kind were first patented in the 1870s.1 It took some decades before the term became common parlance: the Oxford English Dictionary records 1907 as the first year the term “book end” appeared in print.2

A doorstop (also door stopper, door stop or door wedge) is an object or device used to hold a door open or closed, or to prevent a door from opening too widely. The same word is used to refer to a thin slat built inside a door frame to prevent a door from swinging through when closed. A doorstop (applied) may also be a small bracket or 90-degree piece of metal applied to the frame of a door to stop the door from swinging (bi-directional) and converting that door to a single direction (in-swing push or out-swing pull). History Formally-produced doorstops trace their history to the 18th century in Europe, becoming widely manufactured in Europe in the early 19th century. By the mid 19th century, manufacturing had primarily moved to the United States.[1] Despite their early manufacturing, credit for the invention of the doorstop is usually granted to Osburn Dursey, an African Americans inventor, in 1878. The doorstop was Dursey's most famous invention and he received a US patent, number 210,764, for the invention.[2] Usage Holding doors open A door may be stopped by a doorstop which is simply a heavy solid object, such as a rubber, placed in the path of the door. These stops are predominantly improvised.[1] Historically, lead bricks have been popular choices when available.[3] However, as the toxic nature of lead has been revealed, this use has been strongly discouraged.[4] Another method is to use a doorstop which is a small wedge of wood, rubber, fabric, plastic, cotton or another material. Manufactured wedges of these materials are commonly available. The wedge is kicked into position and the downward force of the door, now jammed upwards onto the doorstop, provides enough static friction to keep it motionless.[5] A third strategy is to equip the door itself with a stopping mechanism. In this case, a short metal bar capped with rubber, or another high-friction material, is attached to a hinge near the bottom of the door opposite the door hinge and on the side of the door which is in the direction that it closes. When the door is to be kept open, the bar is swung down so that the rubber end touches the floor. In this configuration, further movement of the door towards being closed increases the force on the rubber end, thereby increasing the frictional force which opposes the movement. When the door is to be closed, the stop is released by pushing the door slightly more open, which releases the stop and allows it to be flipped upwards. A newer version of equipping the door with the stopping mechanism is to attach a magnet to the bottom of the door on the side which opens outward which then latches onto another magnet or magnetic material on the wall or a small hub on the floor. The magnet must be strong enough to hold the weight of the door, but weak enough to be easily detached from the wall or hub.[6]